Site Specific: The Erechtheion

Mariza Daouti on The Erechtheion, Athens

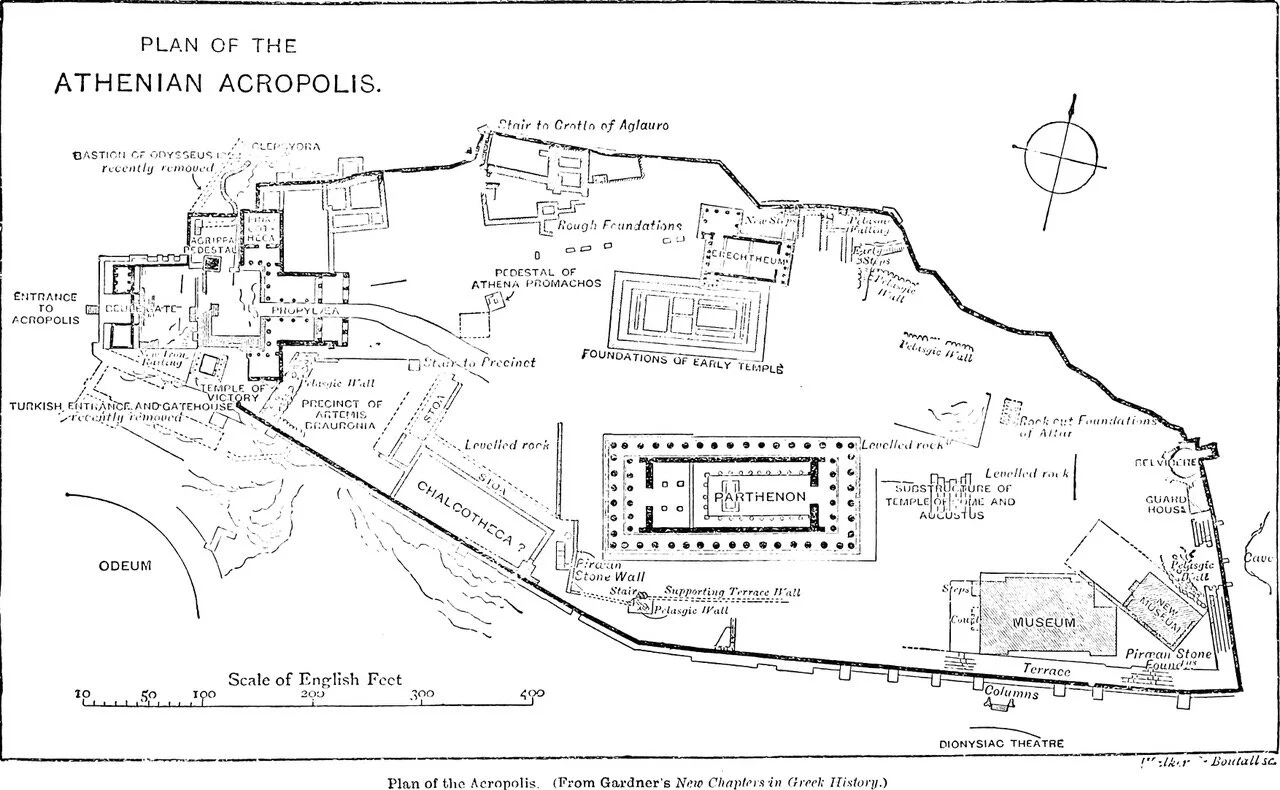

MD The Erechtheion is a small, curiously complex ionic temple on the northern side of the Acropolis hill. The white marble building that survives today dates back to the 5th century BC and formed part of the larger Acropolis project, a material manifestation of the victory of Athens in the Persian wars, its leadership in the Delian league and its achievements in culture, politics and public life.

Its untypical plan is believed to derive from two parameters: site constraints linked to religious requirements and historical inevitability, as its construction was interrupted by the outbreak of the Peloponnesian war.

The challenge for the architect, who is considered to be Mnesicles, to whom the Propylaea is also attributed, was manifold: The building was intended to be placed on a slope at the edge of the hill, next to the remains of a Doric temple; older than the temple was a Mycenaean palace which retained the tomb of the first king of Athens, Cekrops; the old temple of Pandrosus also stood in the way, and nearby rose Athena’s sacred olive-tree, its branches overspreading the altar of Zeus Herceius, all of which were enclosed by a high wall that ran along the west and north sides.

At the same time, Athens going to war with Sparta held back the progress of the works, which instigated a readjustment of the design. The formidable Caryatid porch on the south side of the temple, is actually thought to be a problem-solving feature caused by the reduction in the scope of works.

The Erechtheion was complex in form as well as in religious content. The western part of the Erechtheion was dedicated to the worship of Athena Polias, while the eastern part was devoted to Poseidon-Erechtheus. Sacred spots devoted to different deities, including the tomb of Cecrops and Erectheus and a saltwater spring, co-existed in one building.

In contrast with the magnifying presence of the Parthenon, the Erechtheion is less imposing and more informal, with courtyards, porticos, multiple orientations and diverse features, that constitute weak boundaries between inside and outside, daily life and divine order.

Turbulent history enriched its multifaceted character over time, transforming it both in content and architectural form; while its use was adapted from a temple to a Christian church in the 7th century to a Turkish house in the years of Ottoman rule, the building was also restored many times after suffering severe damages in various historical sieges of the city. With Greece’s independence in 1830, all remaining layers of intermediate history were wiped out, and the ruinous building was turned back to its primary form, followed by more intrusive restorative attempts in the early 1900s.

Finally in 1975, the Acropolis Restoration Service was established; rendered as a ‘rescue operation’ that aimed to undo the damage caused by the errors of previous restorations. The restoration team was formed of young scholars, architects, civil engineers, chemical engineers and an archaeologist, all working under the supervision of experienced academic professors.

A multi-lateral approach was sought in order to determine the most suitable interventions both from a heritage and structural perspective, hence detailed preliminary studies were submitted and a large number of national and international specialists were consulted at every stage of the works. Despite the lack of experience and basic infrastructure for the work of this kind and scale, a series of pioneering techniques and materials were applied and the restorative works now form a precedent in ancient monument preservation.

![Mavrommatis, S., The Erechtheion [Το Ερέχθειο], The photographic documentation of the restoration works of the monuments of the Athenian Acropolis [Η φωτογραφική τεκμηρίωση των έργων αποκατάστασης των μνημείων της αθηναϊκής Ακρόπολης], Chartes magaz…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a0c7d458c56a8acd46aba3a/1604568704913-4T321TZF2PE89269VQK2/%2815%29+Caryatids.jpg)