Site Specific: 168 Upper Street

Groupwork + Amin Taha with Webb Yates Engineers - London, 2017

WY 168 Upper Street occupies a former bomb-site on the corner of Barnsbury Street in Islington and rebuilds the missing piece of a 19th century parade which has sat incomplete since the WWII. When transforming the building a number of typical structural solutions were first considered, instead a more elegant and innovative approach was sought which could bring the architecture and structure together into one cohesive form. Contributing to the streetscape this intervention is a 1:1 hollow-cast monument to the memory of the Victorian terrace which previously existed on the plot, complete with flaws and mistakes that highlight the nature of misremembering.

The original building at 168 Upper Street was conceived as one of two end pavilions on a Palladian-inspired urban block, consisting of ground-floor shops and townhouses above. It stood on the site from the mid-1880s until it was significantly damaged during WWII and eventually demolished in its entirety. Remaining empty until Aria, a local design and furniture retailer purchased it in 2012.

While the architect wanted to remember the previous Victorian building, modern standards – thermal performance, progressive collapse, and so on – made it virtually impossible to replace like for like, and a different approach was required. The building’s appearance was dictated by the height, proportions and Victorian details of the original building, helping to restore the symmetry of the block but contemporary fabrication tools left a distinctly contemporary mark on the new building.

Given the good condition of the remaining block a legitimate design solution to restore 168 Upper Street would have been to rebuild it as a mirror image of its opposite end. Instead, rather than attempting a neoclassical restoration that perfectly replicates the original building with traditional materials and construction techniques, the form was conceived and built using contemporary construction and fabrication processes.

A computer model of the ‘existing’ building was built by studying historical maps and site photographs and carrying out a three-dimensional point cloud laser survey of the site and the building’s mirror twin that still stands on the southern-most end of the block.

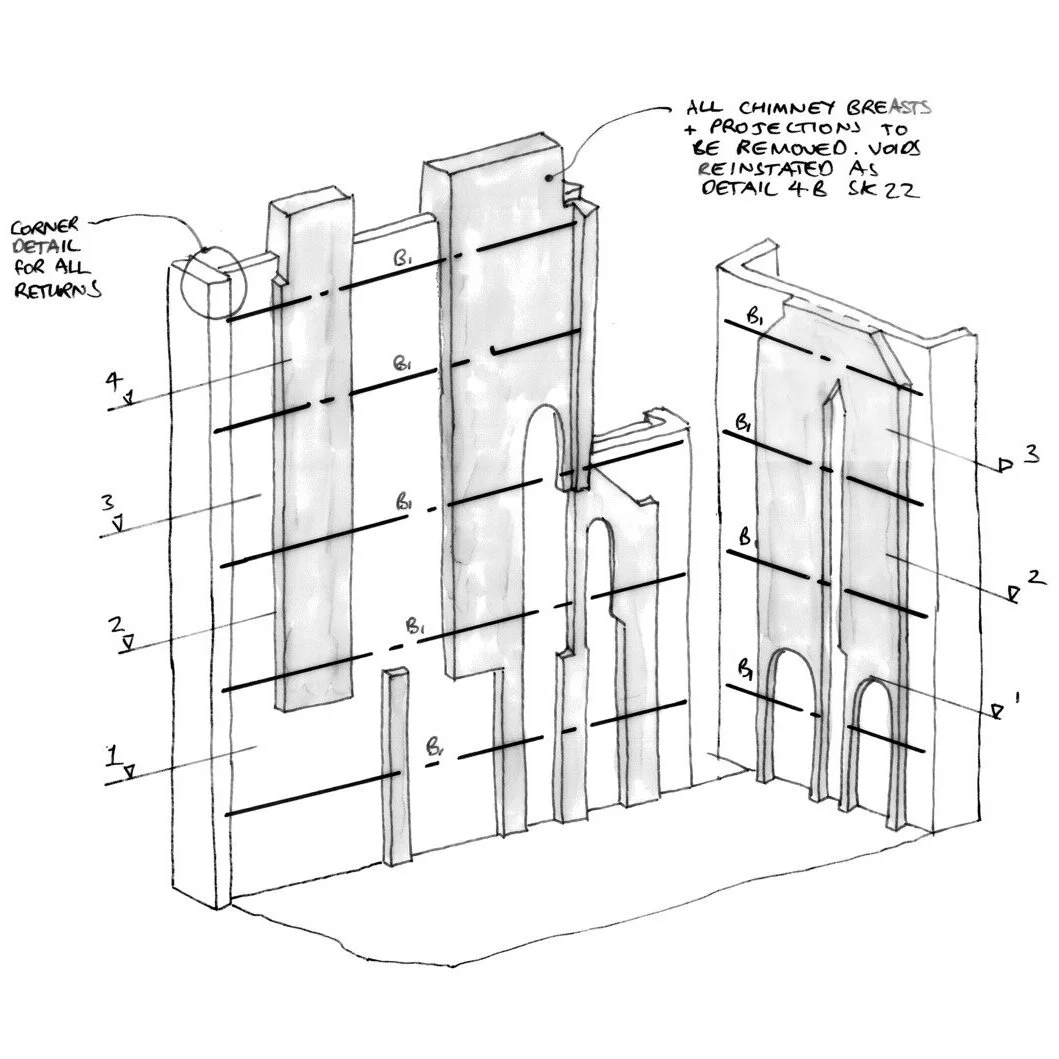

With this information, the building – including its external mouldings, window surrounds and features as well internal skirting, dado rails, cornices and anaglypta wallpaper - was digitally reconstituted and then broken down into 300 sections, ready to be rebuilt. But while these details of the original building are remembered, the floor plates sit in different places and the windows are cut through the façade, placing contemporary desires for floor to floor zone and window sizes on top of Victorian era details.

With the structure, external and internal finishes, and thermal envelope being created from just one concrete cast, it was critical to produce accurate construction information, as any mistake would affect all elements of the building. The digital fabrication process allowed for creating this level of detail, but it also introduced opportunities for imperfections during the manufacturing process. The translation of the CAD information into the manufacturing equipment resulted in some lost and distorted details; the mark of a tool head is evident having traced against the formwork geometry; even the physical manhandling of the formwork created errors.

A complex mould of unique panels - totalling over 450m2 of CNC-cut expanded polystyrene formwork - was drawn in Rhino, fabricated and then supplied to the contractor to bond to inexpensive plywood. With the CLT floors installed first, the formwork was assembled on site in sixteen 1.2m-high horizontal bands. Once the formwork was assembled, construction continued with day pours of the concrete and terracotta mix for each horizontal band – with the entire perimeter poured in one go each time for both internal and external leaves. Once the concrete was cured, the formwork was first removed by hand and then any remaining polystyrene was soda-blasted off, creating a gentle texture to the façade.

While the outer structural shell alludes to the past, the internal space is contemporary but ambiguous. New internal floor plates are slotted into subtle notches and pad stones that were cut into the existing brick party walls, and new windows appear where required without respect to the older window locations or their surrounding neoclassical detail.

NOTES

Thanks to Malin Persson of Web Yates Engineers for her help in compiling this post.

Images © Timothy Soar, Groupwork + Amin Taha Architects and Webb Yates Engineers.

Published 5th November 2020