Martin Kargruber: Genius Loci

Interview - May 2021

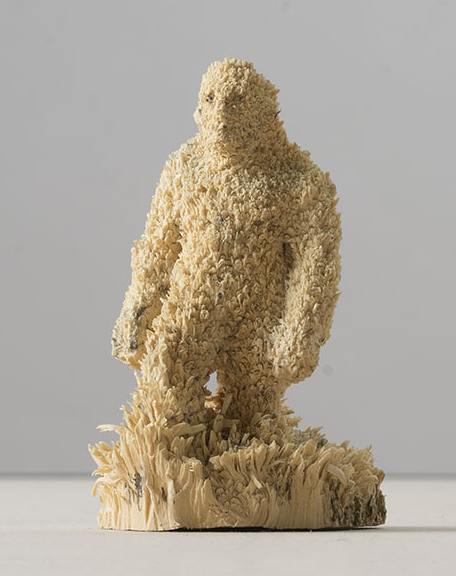

Martin Kargruber is an artist working in Bavaria, Germany whose drawings and sculptures often depict simple figures and buildings set within agricultural settings. These poignant tableaux are expertly carved from single pieces of wood, capturing the ambiguous way in which buildings are both rooted in, but separate from, the landscape in which they stand. Together with his pencil sketches, Kargruber’s sculptures explore a sometimes dream-like territory, situated between craft, place and memory.

Kargruber has been working as a sculptor since the 1980’s and has exhibited internationally, most recently at the Neue Sammlung, Munich in 2021.

MK My interest in landscape and architecture was sparked during the time I was about to complete my fine art studies in Munich in the early eighties, sculpture to be more specific. At that time I found myself in an orientation phase, looking for my own form of expression. I wanted to come up with something that was not influenced by the formal features and subject matter of which I was aware of then. This might explain why images came up in my work that were closely related to my origins.

I grew up in, what was then, a very bare valley in South Tyrol. The local culture and architecture was still largely determined by the work of local craftsmen and farmers. Materials were sourced from the close surroundings and used in a very pragmatic way. This is how I became aware of links between the character of a landscape, craftsmanship, technique and the treatment of material.

Inspired by these links, I attempted to create sculptures through a working process informed by the interaction between natural forms of a used material, the working method and the subject matter. The architectural theme suited this approach well due to its impressive appearance in space and its various allusions to my past/biography.

BOTB Woodworking and carpentry must have been a big part of your life growing up.

MK I grew up in immediate vicinity to the carpentry of my uncle and the work on my parent’s farm was also characterised by the handling of wood. Also, many huts, barns and stables are made of wood there. I lived in those places and experienced the surrounding nature during many summers of my childhood while I worked on my parent’s mountain pasture and with relatives.

BOTB Some of the dioramas put me in mind of Giorgio Morandi’s work, where the space between objects becomes very powerful. But maybe in the countryside, and in your work, there’s more of a sense of the buildings being isolated, of there being a surrounding territory in which buildings are somewhat adrift. This emptiness might be closer in mood to de Chirico’s empty town squares maybe, but it’s less of an urban condition and maybe more about the buildings being containers, composed of planes and surfaces.

There’s something very specific about the scenes you depict, they feel like they must be real locations or perhaps particular memories of specific places.

MK Your notions on Morandi and de Chirico are very touching. Both artists are extremely fascinating to me. This is, on the one hand, because of the spatiality between objects, and on the other hand, because of the distinct atmosphere the two painters manage to convey.

Yes, the scenes are related to specific localities. I try and figure out these localities and scenes on behalf of my recollections of their natural appearances while aiming at capturing their distinct atmosphere or an individual connection I might have to them.

BOTB The traces of pencil on the sculptures indicate that you’re outlining forms in advance of cutting and shaping the wood. On the one hand there’s the ‘brute material’ itself and on the other the ‘image’ uncovered within it. Does one of these aspects dominate?

MK The pencil lines are set to figure out measurements and proportions before shaping the wood. During the process of cutting the wood the lines help to come to terms with its shape. Since the pencil lines are traces of the working process, I consider them of equal importance as the marks of a saw or a chisel. Also, I’m fond of one being able to reimagine the genetics of a sculpture while looking at it.

That aside, the raw material in its original form contributes considerably to making sense of the question of how to come to terms with, of how to combine, natural forms and aesthetic design. I can say though that I consider both elements equally important. It might even be the case that keeping the two elements in balance means coming about with a good/satisfying work.

BOTB Your pencil drawings themselves seem as if they could be preparatory work for the sculptures - are some drawings instrumental in that way, done to sketch something out before shaping the wood?

MK Most of the time, I create the drawings on impulse while being immersed in the mood of a specific place or a story line that has come to my mind in the form of an image. This is how I get myself to further engage with the subject matter/motif. Through drawing the respective place or story becomes less abstract.

Thus, the drawings are more of a way to attune myself to the subject matter, rather than formal or compositional studies. Usually, they are created in the run-up to a sculpture. However, there are some drawings that help to get a better understanding of the spatial relations in terms of the sculpture’s web of different shapes.

These drawings are not necessarily created before starting out with the sculpture, but more or less simultaneously to shaping the wood. Some of them develop into a variant of the subject matter. This is often the case while a completed sculpture still lingers with me. In this case, the drawings are works of their own.

Yet, generally speaking, I believe that drawings and sculptures show fundamental differences in terms of the rules of the respective medium. To me, pencil drawings are indispensable to assess the potential of an idea in the process of creating a sculpture. Through the pencil line a marking becomes visible and therefore enables an evaluation, it materialises a thought and saves it from disappearance.

BOTB The way you describe the role of pencil drawing in your work recalls how an architect might work, with the act of drawing as both an exploration and a projection; as a way to reveal ideas but also to translate ideas into something tangible, something specific and material.

There is something fascinating about the way the imagination works when its in relation to something material, like sculpture or house-building; it’s a reciprocal relationship. It reminds me of how you spoke of turning to the landscape of your childhood as you searched for your own form of expression, as if ideas were found in material things. Do you see the landscape and the timber in this way?

MK I think I have drawn upon the landscapes of my childhood because I then believed that this was the only way to find motifs that are free from artistic predetermination. I believed in this because my memories of those landscapes were very vivid and I therefore felt like finding something authentic in them.

The material aspect you are referring to also goes along with authenticity since any of these buildings inhere a vision of an overall connection: local material, its pragmatic use and the traditional artisan technique contribute to the landscape and its architecture’s unity. This is what I found really inspiring about them. By working with wood, I hoped to find a way to convey those impressions in an up-to-date/contemporary way. Therefore, it was not first and foremostly something material I saw in the landscapes of my childhood, but an interplay between form, technique, material and surroundings. Wood is an elementary component in this context.

NOTES

Many thanks to Martin Kargruber for his time and help with compiling this post.

For more on Martin Kargruber’s work visit his website at www.martin-kargruber.de.

Image on the front page: Martin Kargruber, Wind, 2019, limewood, pencil, 15,5 x 22,5 x 23cm

All images © Martin Kargruber

Posted 17th May 2021