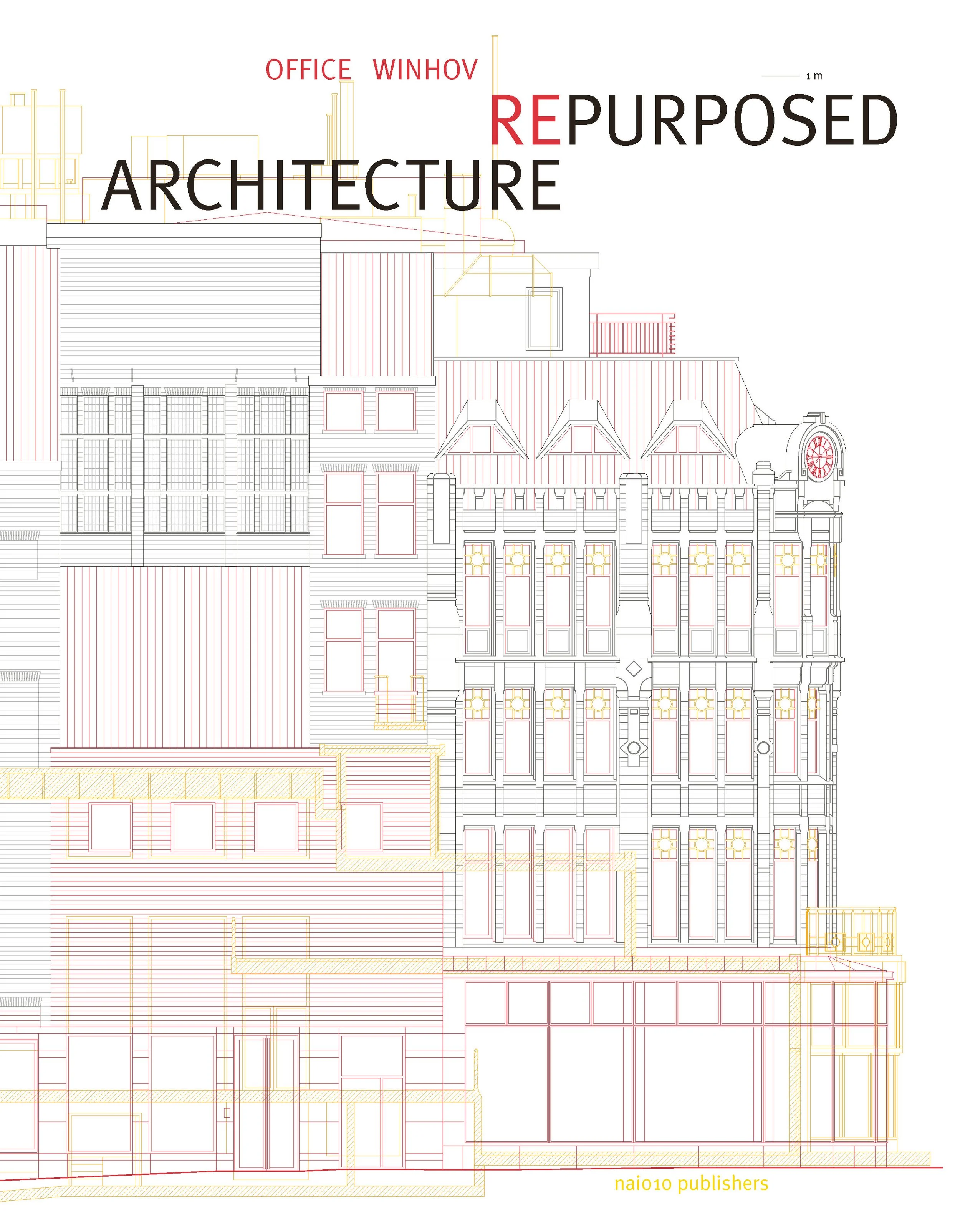

Architecture Repurposed: Office Winhov

Text by Annuska Pronkhorst

Published in October 2024 Architecture Repurposed showcases Amsterdam-based Office Winhov’s adaptive reuse approach which combines contemporary transformations with respect for architectural heritage; charting a course between thoughtless demolition and inflexible adoration of historical buildings.

Below we present the introduction to the book written by Annuska Pronkhorst. Copies of the book are available to buy via the website of publishers nai010.

AP Our perspective on reuse is due for a drastic change in attitude. It is well known that the building sector is largely responsible for the damage inflicted on the climate. It has a proven large share in the consumption of raw materials and energy during production and construction. Preserving and reusing buildings as an alternative to new construction is by far the most sustainable choice one can make; CO2 emissions are the lowest when buildings are renovated. The building industry is becoming increasingly aware of the urgency of this task and is taking steps to make the development and design process more sustainable. The reuse of buildings holds an important key to this task, as we simply cannot afford to waste the CO2 already spent in the past for these buildings. Besides ecological sustainability, the argument of cultural- historical sustainability and continuity is also crucially important. Existing buildings, in all their diversity, create a historical stratification of our built environment and thus give it identity and character. Existing buildings recount the past and provide lessons for the future. In other words, the presence of different time layers of buildings contributes to the spatial quality of our daily living environment. All this raises the question of how, besides making biobased and sustainable construction a matter of course, we can respectfully design for existing buildings so that they are given a suitable new life in the future.

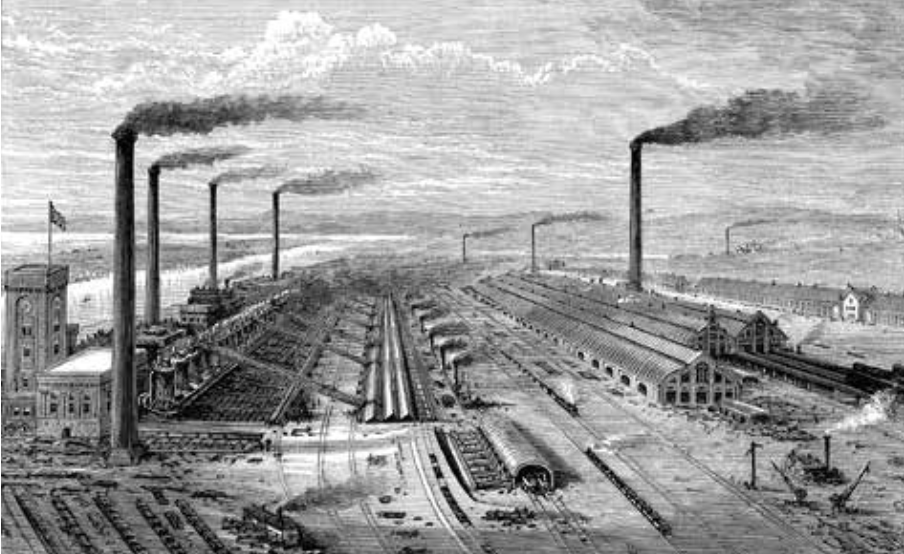

To understand how the architectural world today relates to that which already exists, it is helpful to look back in history. The idea of creating some- thing new from a tabula rasa situation is by no means logical and obvious. The principle of new construction as a replacement for existing structures is a relatively recent phenomenon, normalised only around the beginning of the nineteenth century with the ad- vent of the global Industrial Revolution. Under the influence of rapidly succeeding technical innovations, in which inefficient manual labour gave way to the use of machinery, it became increasingly easy to extract raw materials on a large scale and then reproduce them into building materials such as bricks, concrete and steel. These achievements brought about an immense building boom, but had the detrimental side effect that buildings were increasingly perceived as a commodity rather than a fundamental need. This consumerist attitude with new buildings as its focus has since been elevated to the norm and entrenched in today’s societal system.

Spolia, Church San Procolo, Verona (situation 2016).

Yet building, modifying, reprogramming, dismantling and rebuilding building structures elsewhere has existed since the first humans constructed their own simple structures of stone, clay and wood in the Neolithic period. From time immemorial, buildings have been extended and adapted to the needs and wishes of the moment or to repair damages. People could not afford to demolish a carefully constructed building, dump the building materials obtained and moved with blood, sweat and tears in a landfill and grind them into grit, only to have new building materials rushed in for something new. There are numerous examples in our building history where buildings and materials are reused for a new function, with a well-known and apt example being the Roman spolia. Building materials such as marble and granite but even entire decorative facade parts from ancient cultures were structurally reused and combined in new buildings, within a completely different context. All these historical buildings are always a mix of adaptation and appropriation; like a layered bricolage of building styles and constructions, colours and materials, repairs and scars, revealing something not only about architecture, but also about the use at the time and the historical context in which the buildings were created. Awareness of the relevance of this design and building tradition is not only beneficial for the environment ecologically, but also for the continuation of the rich cultural-historical stratification of our living environment and our civilisation in general.

Nineteenth-century

Iron and Steel Works,

Barrow-in-Furness,

England.

Despite the efforts being made to make building practices substantially more sustainable, clients still often revert to the reflex of new construction instead of reusing and renovating existing buildings. From the perspective of real estate as a commodity, the argument is often raised that demolition of existing buildings is cheaper than repurposing and therefore more profitable at the bottom line. And if it is not explicitly protected as heritage, nothing is stopping its owner from replacing a building that has reached its end economically with a new, and better (financially) functioning one. And even though we have left the period when ‘starchitects’ were admired for their iconic creations behind us now, there is still a strong drive among architects and their clients to leave their artistic and striking signature behind, which is often at the expense of what already exists.

The reuse and transformation of buildings is often seen as a heritage affair, surrounded by the gentle world of

art and culture and hampered by the punitive finger of heritage crusaders who want to protect the crown jewels of our built past at all costs. But the heritage collection of masterpieces covers only a fraction of the existing buildings that should be considered for transformation. There is still a huge reservoir of residential estates, office and business complexes, warehouses, factory buildings and schools, from various construction periods that are in need of a new future due to vacancy, dilapidation or insufficient energy performance. The burden of proof for demolition/new construction is definitely shifting around. Whereas

it used to be limited to the cultural- historical importance of a property, the widely felt need for sustainability now dictates a ‘don’t demolish unless there really is no other way’ attitude. It is important for the design and development disciplines to relate differently to existing buildings, whether they are listed heritage buildings or not.

TO REPURPOSE

But how do you, as an architect, carefully relate to the existing? How can you use design to give new meaning to the mundane built past on the one hand, or the outstanding on the other? Not all buildings are the same. Thankfully, education is increasingly concerned with the reuse task from different perspectives and disciplines, so the future generation of architects will probably not know any different. But at the same time, there is still a gap between heritage and new construction in the daily building practice. Heritage transformation is often still a sum of multiple, often opposite disciplines. It generally consists of renovating the protected monumental part by the restoration specialist and separately adding a contemporary and stylistically different layer by another expert. This is the way people have been trained in the modernist tradition.

Office Winhov is part of a group of like-minded architects that explicitly work with less rigidly delineated briefs and deliberately operate at the intersection of heritage, architectural history, and new construction. Adaptive repurposing of architecture, whether it concerns a seventeenth-century landmark or a run-of-the-mill 1980s office complex, is central to their design practice. In doing so, they try to distance themselves from the customary reuse and restoration architecture in which the new distinguishes itself from the old in contrasting ways. After all, the old and the new are not separate worlds, as building history shows us.

The publication Architecture Repurposed by Office Winhov shares its thinking and methods regarding reuse and transformation with the reader, expressing them concretely through the presentation of a number of realised projects. The projects have been carefully selected as they each tell a different story in their own right and represent different tasks and specific approaches. Sometimes these involve monumental specials, but actually that does not really matter. The chosen approach and treatment apply just as much to young heritage as to the non-listed, more common building stock. For each project, this book includes more floor plans and cross-sections than usual to give the reader a detailed insight in the applied choices, intervention or approach. Sometimes it involves major interventions on the existing, which will no doubt have raised eyebrows among conservative heritage professionals. But in such cases, Office Winhov is always confident, because it is supported by its deep knowledge of the DNA and spatial logic of a building and its past. Sometimes, it conversely takes a cautious approach to its work, aware of its modest position as an architect in the long and layered history of a building that already has several authors. The publication does not advocate a ban on demolition. If a building really no longer functions as it should then it should be replaced, albeit as cautiously as possible. Instead, the book is a plea to look and observe more closely, to come up with a more in-depth analysis, to gain a deeper understanding of the spatial design and logic and thus the functioning of a building, to acquire more knowledge and insight regarding historical building layers and the materials and colours used. To then use the obtained knowledge to figure out what new programme or interventions the building can handle in the new situation, almost as an inevitable consequence. This attitude offers a more respectful alternative to the design and develop- ment approach that is instead based on imposing a pre-calculated programme on an existing building, but which in practice often mismatches to such an extent that the original architecture has to be demolished as a result.

Architecture Repurposed is an optimistic book that encourages thinking about the value of existing architecture, about how to deal with the built past, about the definition of originality and authenticity. It allows colleagues to look at reuse through different eyes, and encourages them to use the knowledge they have gained to work with buildings that until recently might have been ignored or considered less valuable. However, repurposed expressly means more than just adapting the use of a building for another purpose through design, and in a sense, it also stands for the redefinition of Dutch architecture. The book underlines the need to bid farewell to the unsustainable demolition/new construction reflex and the urge to make grand, spectacular architectural gestures, and proposes a new course in Dutch architecture with the presented design attitude towards the existing as an alternative.

Demolition of a Pruitt-Igoe building (Minoru Yamasa- ki, 1951–1955), St. Louis, Missouri, United States, April 1972.

NOTES

Many thanks to Vivian Beekman at nai010 and Karen Willey at Office Winhov for their help with compiling this post. The book can be purchased here.

Postd 22nd November 2024.